Quality private health care is within Hong Kong’s grasp, if the government is willing to regulate

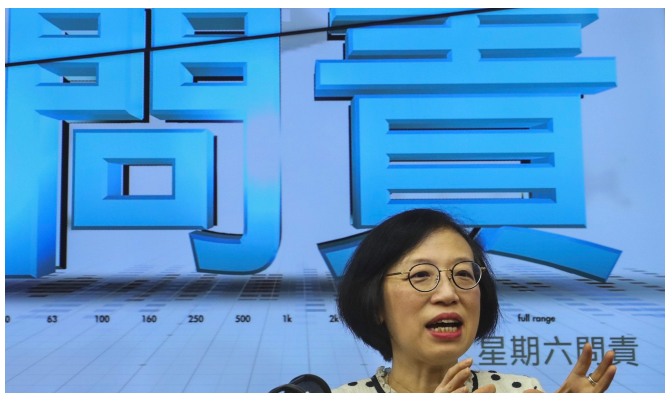

Thalia Georgiou says there are numerous fixes that can make private health care more affordable and relieve pressure

Thalia Georgiou says there are numerous fixes that can make private health care more affordable and relieve pressure

on public providers, if the government supports those willing to reform

After almost a decade in the making, one might expect that the government’s flagship voluntary health insurance scheme would be readied to drive fundamental improvements to Hong Kong’s private health care landscape. The scheme was supposed to create a product that was “entry-level”, comprehensive and priced to attract broader market reach. This was a good vision. As the Hospital Authority creaks along with capacity as high as 130 per cent and waiting times soar to levels rarely seen in developed countries, there couldn’t be a more urgent need for an effective, accessible private care system to alleviate overburdened public providers.

It is therefore disappointing that the most recent release of the proposed scheme’s benefits schedule indicates that the final product will not only lack comprehensiveness but is likely to expose policyholders to unacceptably high risks of payment shortfalls. In many cases, the proposed benefit limits would not be sufficient to cover even half the costs of hospital treatment at today’s prices. That’s a big bill for someone to pay, and worse if they didn’t know it would occur. Insurers and providers alike will doubtless encounter many angry, vulnerable policyholders confused about their coverage and unable to meet the costs of their share. The government, in promoting and offering tax incentives for the scheme, will also bear responsibility for a group of policyholders who feel severely short-changed. It’s a recipe for reducing confidence in the private system, not enhancing it.

The scheme, like all attempted health care reform in Hong Kong’s recent past, seems set up to fail before it gets out of the door. The reasons are simple; providers and insurers have not been encouraged or supported to work collaboratively to create better, more cost-effective ways of delivering health care. Instead, a broken system has descended into transactional conflicts; providers are painted as self-interested individuals motivated only by greed and insurers as corporate giants motivated by rationing care. These are misperceptions; the behaviour we see is the result of people playing within the rules of the game. The problem is that the rules should have been updated long ago to allow systems and behaviours to change. Dealing with major structural issues is consistently put in the “too hard to tackle” box. Change will always bring opposing views; we need political will, support, leadership and frameworks to resolve conflict, not to sweep it under the carpet.

What you need to know about this year’s unusual winter flu surge in Hong Kong

There are many improvements that could be made. Currently, neither insurer nor provider are required to publish data on key quality indicators – readmission rates, surgical outcomes or even length of stay. This restricts the public from accessing information on the quality of their care and hinders them from selecting (and rewarding) higher-quality providers. This is easily rectified; the data already exists but needs to be independently assured and standardised. Many hospitals are ready and willing to publish data, but can’t without comparators – a system approach is needed.

How Hong Kong’s private hospitals are failing their patients

Similarly, there are flaws in pricing models. While most of the developed world has moved towards prospective payment methods (true packaged pricing with guaranteed certainty), Hong Kong operates on a fee-for-service basis universally acknowledged to drive unnecessary activity and increase costs. As a patient recently advised, “one doesn’t need to be an economist to know that putting doctors in the conflicted position of being both prescriber and dispenser of medicines will lead to huge overprescribing”.

It’s inevitable that discussions on pricing will stir protectionism, but in practically every other major developed market newer, better pricing models have emerged to deter oversupply and have attracted, not deterred, individuals to use private care. Done properly, it can be a win-win. There are willing providers; but this requires technical support, investment in IT systems and a period of supported transition. For most small private hospitals, the cost of making this change is out of reach – it requires government support to mobilise and regulate.

Hong Kong nurses pushed to breaking point as city tackles winter flu season, union chief says

It is a rare for a health system to ask for more regulation and more support; but conversations with both insurers and providers suggest this is both needed and wanted. We all want a vibrant, fully utilised private health care system, and all want health reform to support this. Sadly, unless the insurance scheme and its sister policies are radically rethought, the chances of the situation worsening are very high. Ultimately, our population loses out. Having to wait, as some do, many years for life-changing care is deeply distressing. We have the opportunity, capability and perhaps moral obligation to do better; I hope our new government drives the much-needed change we want.

By: Thalia Georgiou

Source: http://www.scmp.com/